In a study of orangutans living on the Indonesian islands of Borneo and Sumatra, scientists from Duke University and the University of Zurich have found what they say is the first demonstration in primates of an evolutionary connection between available food supplies and brain size.

Based on their comparative study, the scientists say orangutans confined to part of Borneo where food supplies are frequently depleted may have evolved through the process of natural selection comparatively smaller brains than orangs inhabiting the more bounteous Sumatra.

The findings "suggest that temporary, unavoidable food scarcity may select for a decrease in brain size, perhaps accompanied by only small or subtle decreases in body size," said Andrea Taylor and Carel van Schaik in a report now online in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Taylor is an assistant professor at Duke's departments of Biological Anthropology and Anatomy and of Community and Family Medicine. Van Schaik directs the University of Zurich's Anthropological Institute & Museum, and he also is an adjunct professor of biological anthropology and anatomy at Duke, where he had worked for 15 years.

"To our knowledge, this is the first such study to demonstrate a relationship between relative brain size and resource quality at this microevolutionary level in primates," they said.

Such a change would provide support for what Taylor called the "expensive tissue" hypothesis. "Compared to other tissues, brain tissue is metabolically expensive to grow and maintain," she said. "If there has to be a trade-off, brain tissue may have to give."

"The study suggests that animals facing periods of uncontrollable food scarcity may deal with that by reducing their energy requirement for one of the most expensive organs in their bodies: the brain," van Schaik added.

"This brings us closer to a good ecological theory of variation in brain size, and thus of the conditions steering cognitive evolution," he said. "Such a theory is vital for understanding what happened during human evolution, where, relative to our ancestors, our lineage underwent a threefold expansion of brain size in a few million years."

In their study, Taylor and van Schaik focused on several varieties of orangutans, an endangered primate closely related to humans.

Members of the orang species inhabiting Sumatra, called Pongo abelii, live in the island's most favored environment, where soils are best for growing the fruits they most like to eat. "They'll eat fruits as often as they can, and they'll travel farther away for them if not nearby," Taylor said.

Sumatra also appears to be less subject to periodic "El Niño" climatic fluctuations that disrupt vegetative growth on other islands in the Indonesian region, the researchers' report said.

The scientists found that the nutritionally well-off Sumatran orangutans differed most strikingly from Pongo pygmaeus morio, one of the three subspecies occupying the island of Borneo. The morio subspecies lives in the northeastern part of the island where soils are poorer, access to fruit is most iffy and the impact of El Niño events can be significant.

Those factors "converge to produce an environment for orangutans of eastern Borneo that is at times seriously resource-limited," the scientists wrote. During extensive fruit-short periods, the animals have to "resort to fallback foods with reduced energy and protein content, such as vegetation and bark," they added.

In previous studies, reported in the April 2006 issue of the Journal of Human Evolution, Taylor found evidence that orangs living in Borneo's northeast have jaws that are better able to handle tougher varieties of food than orangutans in other parts of Borneo or Sumatra.

This improved feeding efficiency, coupled with a relatively small brain, would enable such animals to adapt to their conditions by both maximizing their resources and conserving energy, she said.

In addition, studies by van Schaik and other scientists have suggested that Borneo's morio orangs bear offspring more frequently than do Sumatra's orangs. Such relatively short intervals between births could themselves be tied to smaller brains in such higher primates as orangutans, van Schaik and Taylor wrote in their current report.

"Larger-brained apes have slower-paced life histories," they said. "Assuming selection is acting on brain size, life history is prolonged because development of larger brains require more time."

Their previous work led Taylor, an anatomist who studies bones, to begin collaborating with van Schaik, a field biologist who studies living orangs in the wilds, to address the question of whether nutrition, brain size and interbirth intervals might be linked.

Other scientists working in the 1980s had found no differences in brain size among orangs from Borneo and Sumatra, Taylor said. But that work sampled animals only from west Borneo and not from resource-limited east Borneo, she added.

In their own studies, as well as in studies by other researchers, "we see greater anatomical differences amongst the Bornean populations than we see between the Bornean and Sumatran populations," Taylor said.

In addition to having physical differences, Bornean orangs also inhabit areas that vary more ecologically than do comparative orangutan habitats on Sumatra. "The eastern parts of Borneo suffer more from El Niño-related droughts than parts of western Borneo," the scientists wrote. "The effects of El Niño on tropical rain forest composition and diversity are also more marked in eastern compared to western parts."

So Taylor and van Schaik undertook "a comprehensive re-evaluation of brain size among all orangutan species and subspecies," they wrote.

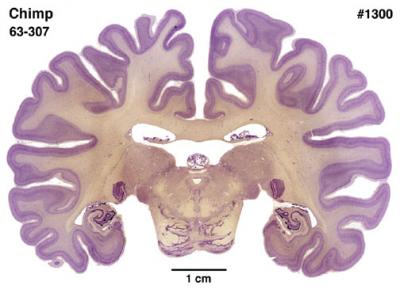

Since they couldn't measure brain size in wild, living members of these endangered animals, Taylor sought out skulls from museums and other sources. In all, they compared 226 adult specimens from the four distinct populations occupying Sumatra and Borneo.

Among these populations, orangutans of the Pongo pygmaeus morio species on Borneo "consistently exhibit the absolutely and relatively smallest cranial capacity," the researchers concluded. Although the researchers found reduced brain sizes in both male and female orangutans, the differences within the small group of animals studied were statistically significant only for the females, they noted.

As to what may cause the gender difference, the researchers note that female morio are notably smaller than their male counterparts and that they generally are at greater risk for nutritional stress because of pregnancy and lactation and their smaller homes ranges.

"The general scenario supported by these results, then, is that an increase in the frequency of uncontrollable periods of low energy intake in one part of the orangutan's geographic range selected for a reduction in brain size," the researchers said.

Similar evolutionary pressures within resource-poor environments also may explain the smaller-than-normal brain size of a controversial 18,000-year-old skull recently found on the Indonesian island of Flores, Taylor and van Schaik said in their article.

In announcing the find in 2004, the skull's discoverers suggested that the small-brained specimen represented a new dwarf early human species that somehow survived until fairly recently. Critics argue that it actually is a modern human afflicted with microcephaly, a genetic disorder characterized by an abnormally small head and an underdeveloped brain.

Web address: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/10/061023192505.htm